Samurai Song by Robert Pinsky

Monotony is a big risk with a poem like this, considering the repetitive “when…then…” structure. Think about how redundant the poem would get if all of it were organized like the second stanza, with each line containing a complete “when…then…” thought. To combat this, Pinsky uses line breaks to keep the reader off-balance.

Samurai Song

By Robert Pinksy

When I had no roof I made

Audacity my roof. When I had

No supper my eyes dined.

When I had no eyes I listened.

When I had no ears I thought.

When I had no thought I waited.

When I had no father I made

Care my father. When I had

No mother I embraced order.

When I had no friend I made

Quiet my friend. When I had no

Enemy I opposed my body.

When I had no temple I made

My voice my temple. I have

No priest, my tongue is my choir.

When I have no means fortune

Is my means. When I have

Nothing, death will be my fortune.

Need is my tactic, detachment

Is my strategy. When I had

No lover I courted sleep.

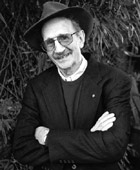

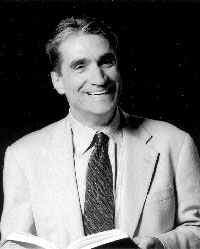

Robert Pinsky was born in Long Branch, New Jersey, in 1940. He is the author of six books of poetry and is currently the poetry editor of the weekly Internet magazine Slate. Pinsky teaches in the graduate writing program at Boston University, and in 1997 was named the United States Poet Laureate

Robert Pinsky was born in Long Branch, New Jersey, in 1940. He is the author of six books of poetry and is currently the poetry editor of the weekly Internet magazine Slate. Pinsky teaches in the graduate writing program at Boston University, and in 1997 was named the United States Poet Laureate